The truth about dogs and cats 5

It’s been a full-on year here at T&S: we’ve covered obesity, domestic violence, feminism in universities, female serial killers, science, language and more. But there’s one debate we’ve hesitated to tackle: are dogs the new feminist cats?

Media commentary on this issue has been dominated by the liberal argument that companion-animal preferences are a matter of individual choice. For radical feminists, though, the personal is always political. So, as we head towards a new year, we have invited two radical feminists with sharply differing views to explain where they stand on one of the most important–and most divisive–questions facing our movement today. Planet Cath explains why she believes a dog is woman’s best friend, while Finn Mackay makes the case for staying true to our foremothers’ feline traditions. Their feminism will be about pets, or it will be bullshit.

Planet Cath: ‘Dogs are the number one companion for feminists’

Traditionally, feminists have been drawn to our feline friends. We believe that cats have all the qualities a feminist needs. They present as independent, aloof yet affectionate when needed. They aren’t needy, or demanding of your time, or wanting more than you can give. I say we’re kidding ourselves. Cats are not a feminist pet. They have no sense of community or sisterhood. They will destroy anything and everything to sharpen their claws, not caring that it’s a much loved piece of furniture. Cats don’t care. They don’t care about other cats, and they don’t care about you.

Feminists need to face the truth. We kid ourselves that our cats love us, wait for us, are happy when we return home from work. Not so. Cats are only interested in food and heat stealing.

In fact, the best pet for a feminist is a dog.

I stand before you a long time cat owner, but recent dog convert.

I have to nail my animal colours to the mast now; it’s all about the dog.

Not that I don’t love my cats. They are each, in their own special way, amusing and entertaining. They have their own personalities and characteristics, and a couple of them aren’t averse to a cuddle. But my Basil? Basil literally jumps into your arms. Just coming back into a room you left ten minutes ago is a joy to him. “Where have you BEEN?” he cries. “I thought you had gone FOREVER!!!”

He runs around in circles, leaping with joy, and then brings you a present. I admit, the presents are not necessarily the best ones I’ve ever had. A well-chewed ball or soft toy, often covered in spit or dirt. However, I will take that over my cats’ last offering, which was a dead rat, insides ripped out and deliberately positioned on the kitchen floor en route to the kettle for the optimum, barefoot-6am-half-asleep effect.

Cats are affectionate, don’t get me wrong. But they are not willing companions. They are independent, often aloof and walk their own path. They are stubborn, difficult to engage and refuse to do anything that might make your life easier.

Whereas dogs love nothing more than pleasing you. They will watch TV with you (literally sit and watch TV), accompany you on walks, listen to your problems with an interested expression, and treat every word you utter as a meaningful statement to be considered and obeyed.

But you know, it’s more than that. For the single lesbian, dog-walking opens up a whole new potential dating world. You can’t walk your cat, but take your dog out to the park, armed with a variety of toys, and watch women flock to you. In just a few weeks, we’ve made friends with Lisa and Rosie, Emma and Alfred, Karen and Jack. We are all on the local park at 7am, staggering around half asleep, clutching flasks of tea and watching our dogs run and play like proud mothers.

There’s no doubt in my mind that dogs are the number one companion for feminists. If you don’t believe me, take a good look at your cat right now. Chances are, they are washing themselves, seemingly ignoring you but actually waiting for you to leave the room so they can help themselves (aka steal) to the milk jug you’ve left out. Basil, on the other hand, is gazing at me with adoring eyes and waiting for the signal that he can come and snuggle up and lick my ear.

Women. You know I’m right.

Finn Mackay: ‘Cats are enlightened spiritual beings’

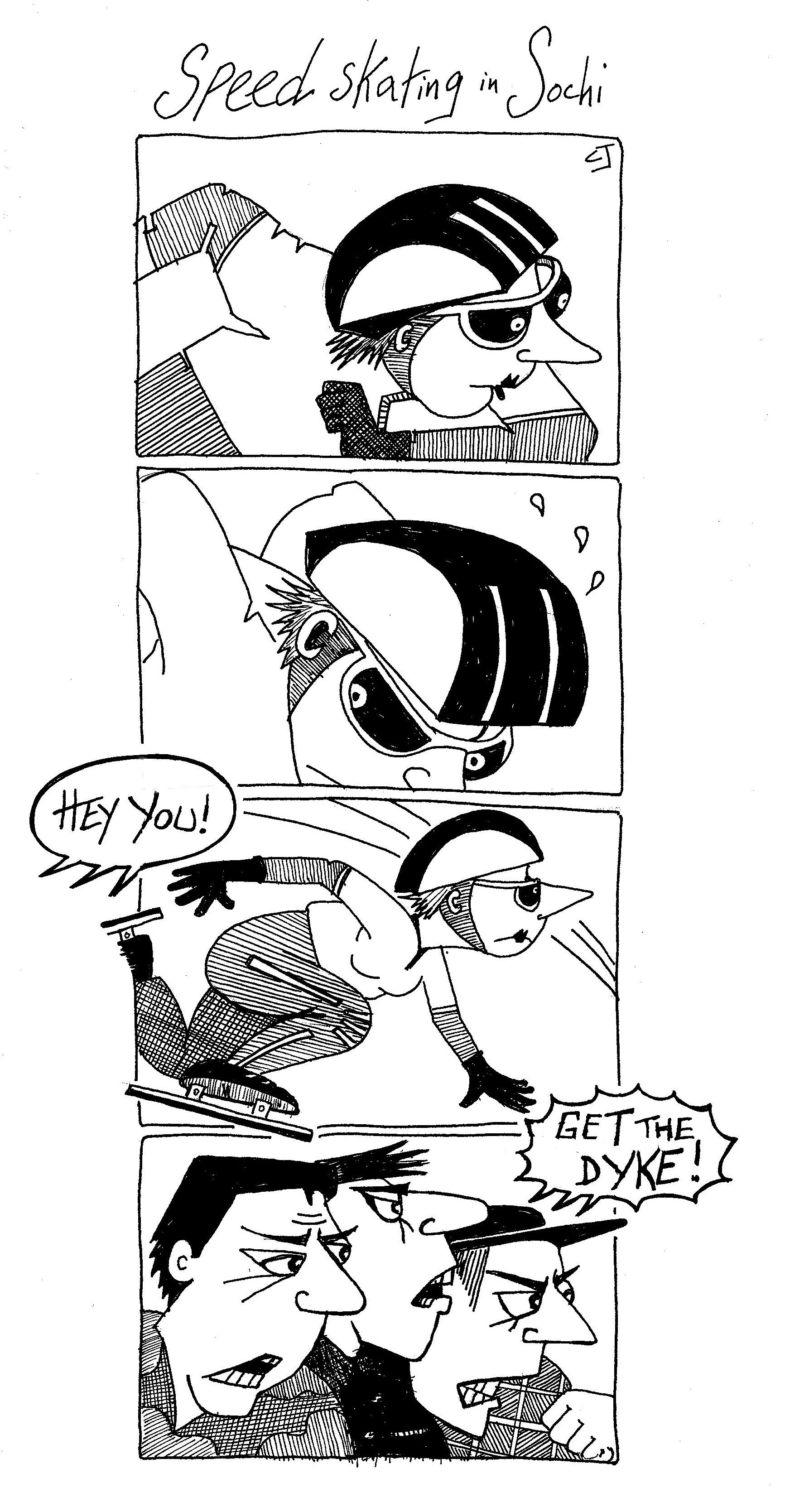

Let’s face it, we all know the real problem with dogs. Do you have a property without a garden? Don’t live near a park? Do you work a normal job rather than running your own self-employed equalities training and consultancy business from home? Are you required to be out of the house or away for any length of time ever? Do you live in a flat and have a fancy for Huskies and Alsatians? If so, then all well and good; fascinating. A person of your standing will be well aware, then, that the main problem with dogs is their support for the capitalist patriarchal military and state industrial complex.

That’s right. If only Battersea could address this, their kennels would empty in a flash. If you for any second doubt this fundamental flaw, just ask yourself – have you ever seen a police cat? A bomb disposal cat? A drugs sniffer cat? No. Unlike their equine and canine fellows, cats have never sold out. Amongst the liberals, the sell-outs and the ‘just following orders’ types, they stand tall, sometimes even nine to ten inches high from paw to ear.

A cat is the perfect Feminist companion, and will fit right in to any commune, caucus or conference. We are uniquely placed to live with cats and, in turn, they mirror our own behaviours and proclivities, meaning that we can be comfortable around their all-too-familiar habits. Just like Feminists, cats are triggered by almost everything. Bin bags, for example. Hoovers. Car journeys. Vets. Which of us can honestly say she has not felt the same at some point over our life course? Luckily we are familiar with the proactive use of quiet rooms, mindfulness and healing circles, and we share this with cats, who are impressively skilled at being quiet and mindful; we could all learn a thing or two from them. My cat is in fact running a workshop on this over International Women’s Day next year; watch this space for entry requirements and inclusivity statement.

If you are still doubtful as to the merits of cats, it is worth pointing out that it is precisely at this time of year that cats really come into their own. Like us, cats display their distaste for the seasonal consumerist atrocity that is Christmas. If ever you should slip, and be seduced by the globalised nothings on offer in the stores, which can happen when suffering from postmodern anomie, a cat will tear down your Christmas tree for you and shred your presents, thus helpfully reminding you of your principles.

Like Feminists, cats are enlightened spiritual beings. They walk their own path, the path of the heart. This means they don’t need to be taken out for walks on a lead, like the less advanced canine. While they are walking their own walk and delicately tipper-tappering their own path, they will not roll in fox poo or rabbit entrails. This is a major plus.

Cats are certainly clean of habit, and clean of coat. They do not smell of dog. This is very important. Glade plug-ins were invented by dog owners. Cats on the other hand, like the Buddha, are odourless. This means they are ideally placed to fit in with your home rituals, such as Shamanic smudge stick cleansings, and they may even be qualified to lead minor domestic shadow work for example–unless they find shadows triggering or over-stimulating, which some do.

Unlike dogs, but like vaginas, cats are self-cleansing. Very occasionally however, cats may shed some fur. This can be gathered up and used for jumpers, merkins or art installations. In addition, while dogs must always toilet outside, despite most Western homes having the imperialist legacy of indoor plumbing, if need be cats can take care of their own bodily waste via the provision of a small recycled plastic box and some environmentally friendly and tree conscious woodchip. Like a gift, cats offer up to us the experience of managing this waste as a symbolic reminder of own bodily liminality, and challenge us to face Kristeva’s feminist theory of the abject.

Like Feminists, cats are independent, unlike simpering dogs. This means we can respect cats, and that is so important in a companion animal. As we must always eschew all those creatures who continue centuries of oppression by demanding a maternal reaction, it is vital that we turn to a pet we can look up to rather than look after. This is why cats have infamously been the totem of choice for self-respecting lesbian feminists the world over. Sisters, some traditions are worth maintaining, feeding, worming and flea treating. Get a cat, you’re worth it.

You can follow @PlanetCath and @Finn_Mackay on Twitter. Their non-human companions have so far elected not to maintain a social media presence.