Jeremy Corbyn: Two views

Jeremy Corbyn’s election as leader of the Labour party has sparked heated discussion amongst feminists about whether or not the new Labour politics is good news for women. Here we publish two pieces which take opposing views of this question.

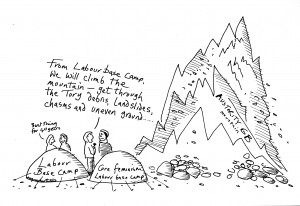

Cartoons by the amazing Angela Martin.

The rise of the dick-swingers?

Rahila Gupta argues that knee-jerk feminist anti-Corbyn reactions are unwarranted and misplaced.

Feminists of all persuasions seem to be divided about whether or not the rise of Jeremy Corbyn is a blessing or a curse for women, and much of the negative reaction seems to come from a historical suspicion of the male left. However, I have been particularly dismayed by the kneejerk reaction of some radical feminists to the rapid ascent of Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell to the Labour leadership and shadow chancellorship, who have portrayed this phenomenon as ‘the rise of the dick-swingers’. As far as I am concerned, the recent outcome of the labour leadership election, and the debate that has accompanied it, is one of the most exciting developments in the last 40 years and has enthused me about British parliamentary politics in a way that I didn’t think possible. But this enthusiasm hurts, accompanied as it is by the fear that this challenge to the consensus may be strangled at birth. We have seen how the powers that be in Europe have attempted to stunt the growth of Syriza and Tsipras. The knives are out for Corbyn from every possible direction – the media, the Tories and apparently most of the Parliamentary Labour Party. The last thing  we need is for feminists to jump on this bandwagon. Some of the anti-Corbyn positioning, from radical and socialist feminists alike, is predictably about the jobs (or lack of) for women in the shadow cabinet. Whilst I agree that there should be visibility, equal opportunities and representation for women, surely we should go beyond identity politics and also be asking questions about the policies espoused by the women we choose. I voted for Corbyn and Watson as his deputy on the basis of their record and their politics. Watson was like a hound dog in his determination to expose child sexual abuse in the Westminster elite and holding the Murdoch empire to account. None of the women inspired a similar confidence although I would have dearly loved to give one of them my vote. When the first four shadow cabinet jobs were announced, they had all gone to men, so the clamour grew about this being the same old left politics. When the entire cabinet appointments were announced and slightly more than half were given to women, this was still not enough to please the naysayers.

we need is for feminists to jump on this bandwagon. Some of the anti-Corbyn positioning, from radical and socialist feminists alike, is predictably about the jobs (or lack of) for women in the shadow cabinet. Whilst I agree that there should be visibility, equal opportunities and representation for women, surely we should go beyond identity politics and also be asking questions about the policies espoused by the women we choose. I voted for Corbyn and Watson as his deputy on the basis of their record and their politics. Watson was like a hound dog in his determination to expose child sexual abuse in the Westminster elite and holding the Murdoch empire to account. None of the women inspired a similar confidence although I would have dearly loved to give one of them my vote. When the first four shadow cabinet jobs were announced, they had all gone to men, so the clamour grew about this being the same old left politics. When the entire cabinet appointments were announced and slightly more than half were given to women, this was still not enough to please the naysayers.

Radical feminists have been particularly vocal in their anti-Corbyn commentary, arguing that that his decision not to appoint a woman to any of the four top positions is indicative of how he intends to engage (or rather, not to engage) with feminist concerns. I actually buy Corbyn and Mcdonnell’s view that foreign affairs being perceived as more important than health or education (both these portfolios went to women) is a colonial hangover when Britain is playing a much smaller role in the world. This is the NEW politics. Given the mountain that Corbyn has to climb to build party unity, two of the jobs were kept by Blairites (Hilary Benn and Lord Falconer) who were already in post. John McDonnell, who became shadow chancellor, is absolutely the best person for the job. As MP for Hayes and Hillingdon where Heathrow airport is located, he is indefatigable in his support for refugees and immigrants both at an individual and at a policy level. He is in tune with Corbyn, perhaps even more left-wing than him and if he were to ever become chancellor, I can think of no other person in Parliament who would make the funds available to implement some of the most ambitious pledges to end austerity and deal with violence against women.

Much of what I have seen from feminists appears to be based on ignorance of his policies for women as laid out in his Working for Women document. Here are just a few of Corbyn’s pledges:

- Work towards providing universal free childcare

- Recognise women’s caring roles through tax and pension rights

- Reverse the cuts in local authority adult social care and invest in a national carers strategy, under a combined National Health & Care Service

- Properly fund Violence Against Women and Girls Services and make it easier for women to be believed and get justice.

They want to restore cuts in legal aid which have massively damaged women’s access to justice and ensure that women asylum seekers get proper access to health services. Dawn Foster has written about the potential for positive impact of Corbyn’s policies on women on the Open Democracy site at length so I won’t rehearse all the arguments here. We know how austerity has disproportionately affected women and none of the other Tory-lite candidates had much to say about it until they were pushed to a more progressive position by Corbynmania. By pushing the knife into Corbyn, feminists are damaging their own best interests.

They want to restore cuts in legal aid which have massively damaged women’s access to justice and ensure that women asylum seekers get proper access to health services. Dawn Foster has written about the potential for positive impact of Corbyn’s policies on women on the Open Democracy site at length so I won’t rehearse all the arguments here. We know how austerity has disproportionately affected women and none of the other Tory-lite candidates had much to say about it until they were pushed to a more progressive position by Corbynmania. By pushing the knife into Corbyn, feminists are damaging their own best interests.

That is not to say that there is nothing to worry about in Corbyn’s pro-feminist politics. I have written about the gaps in his manifesto, namely around religious fundamentalism and the sex industry. I attended a hustings at Ealing Town Hall in August in order to challenge him about these issues. As I was there as a journalist, I didn’t get to ask any questions in the hall. Fortunately, a colleague, Sukhwant Dhaliwal from Southall Black Sisters (SBS) urged him to make a statement against religious fundamentalism because it was antithetical to human rights, rocked the foundations of democracy and had a devastating impact on women. He gave an untypically woolly answer saying, ‘we’ve all got views on this’ and invited SBS to contribute to the document.

However, we spotted him outside the hall and detained him for further questioning much to the unhappiness of his son and campaign manager. Apparently an ear infection had temporarily affected Jeremy’s hearing and he had not quite heard the question on religion. He made it clear that he was a secularist and saw no place for religion in politics or in the public sphere such as the provision of violence against women services. I have written about this trend elsewhere when the Home Office contract to POPPY for running a refuge for trafficked women was handed over to the Salvation Army.

I asked whether he would pull the plug on funding faith schools which gave him pause for thought. He felt the system was too entrenched, that perhaps the answer was to deal with it through a change in admissions policy although he accepted that admissions could not tackle the inherently discriminatory nature of faith schools, their lack of commitment to gender equality and the absence of sex education and PHSE classes. He suggested that strengthening local education authorities and their role in defining and providing education in local areas could be another way of tackling this issue.

On the question of prostitution, Corbyn seemed open to persuasion. Niki Adams, of the English Collective of Prostitutes, delightedly claimed that Corbyn opposes the Nordic model which calls for the criminalisation of those who buy sex, the decriminalisation of prostituted women and the development of exit strategies for them. I have not seen any statements by Corbyn himself on it. The fear that Corbyn is typical of many men on the left who see it as ‘sex work’, a trade union issue and an industry which can be cleaned up with the right laws and proper implementation is justified. This is John McDonnell’s Achilles’ heel too. However, Corbyn agreed that without tackling demand, trafficking of women would increase, seemed concerned that the majority of women enter prostitution as children (average age of 15) and offered to meet with survivors of prostitution to talk further about the issues involved. We shall certainly take him up on that offer.

We need to engage with this new force in the Labour party not stand on the side-lines and throw brickbats at it.

After the revolution?

Delilah Campbell ponders the rise of Jeremy Corbyn: is it a triumph for feminism or the triumph of hope over experience?

Last week, I watched the fourth and final episode of the historian Amanda Foreman’s TV series The Ascent of Woman. The episode’s title was ‘Revolution’, and it traced a recurring pattern in the history of modern revolutions, from Paris in 1789 to Cairo in 2011. Women stand beside men (or sometimes in front of them) in the fight for freedom, only to be comprehensively sold out by the leaders of the new regime, who have no interest in the liberation of the female half of the human race: more often they are determined to prevent it. In France, the feminist Olympe de Gouges was executed during the Terror, and French women soon found their position redefined by the Napoleonic code, which was even more restrictive than the pre-revolutionary law. In Russia, Alexandra Kollontai was given the power to make a difference for a while, but ultimately she was removed from her position and forced into exile. Variations on this pattern have been repeated time and time again.

The ascent of Jeremy Corbyn to the leadership of Britain’s Labour Party is hardly to be counted among the great revolutions of world history, but as I watched Amanda Foreman lay out her depressing thesis, I couldn’t help thinking that British feminists are enacting a miniature version of the same old story, enthusiastically supporting a male-led leftist coup without making that support conditional on any kind of commitment to meeting our political demands. Not that such a commitment would necessarily be honoured, of course, but in this case I’m embarrassed by how little feminists seem to expect, and how eager many have been to defend Corbyn whatever he does or doesn’t do.

The ascent of Jeremy Corbyn to the leadership of Britain’s Labour Party is hardly to be counted among the great revolutions of world history, but as I watched Amanda Foreman lay out her depressing thesis, I couldn’t help thinking that British feminists are enacting a miniature version of the same old story, enthusiastically supporting a male-led leftist coup without making that support conditional on any kind of commitment to meeting our political demands. Not that such a commitment would necessarily be honoured, of course, but in this case I’m embarrassed by how little feminists seem to expect, and how eager many have been to defend Corbyn whatever he does or doesn’t do.

I would not say I am anti-Corbyn, and I’m certainly not criticizing the feminists who voted for him in the Labour leadership election. Most of the feminists I know who voted did vote for him: though a couple preferred to support what they considered the best, or least worst, of the women candidates, Yvette Cooper, most felt that women’s interests would ultimately be better served by the anti-austerity politics which only Corbyn represented. What I’m ‘anti’ is the idea that feminists have a duty to act as cheerleaders for the new regime, and that we are not entitled to hold it to account when it acts in ways that do not serve our interests as we define them. For instance, all the feminists I know who voted for Corbyn also voted for Stella Creasy as deputy leader. It isn’t Corbyn’s fault that she wasn’t elected, but if he cared what feminists thought he should have offered her a decent job.

Also, while we’re on the subject of jobs, I’m afraid I don’t buy that line about health and education (portfolios he did give to women) being more important than those pompously named ‘Great Offices of State’ (Chancellor, Home Secretary, Foreign Secretary). To me that sounds like a classic piece of spin, invented to do the same job as the hasty elevation of Angela Eagle when the media started shouting about the absence of women at the top. When that happened, feminists joined in with the chorus of ‘stop carping and give him credit for appointing a Shadow Cabinet that’s half women’. Sorry, but I don’t think feminists should give anyone points for that. Surely in 2015 we ought to be able to assume that any group of people appointed purely on merit will be approximately 50% female. We should cry sexism when that isn’t the case, not say ‘wow, congratulations’ when it is.

Before he was elected, Corbyn put out a policy document on women’s issues which has been positively received by many feminists, and which does tick some important boxes. But it doesn’t cover all the issues that matter to radical feminists, and those of us old enough to remember when the Left Corbyn grew up with had power—in local councils, in trades unions, in the Labour Party—have reasons for thinking we can’t just trust him to do what we consider the right thing. The sexual liberationism of Corbyn’s generation of leftist men has frequently brought them into conflict with radical feminists in the past, and there’s potential for that to happen again in future. John McDonnell, Corbyn’s closest ally and now his Shadow Chancellor, is a vocal advocate for legalizing the sex industry: how long before he tries to make that Labour policy? Corbyn himself was MP for Islington during the time when children in council care were being sexually exploited and abused. It’s not illegitimate for feminists to wonder what he knew, what he did, and what he thinks should be done about it now. But we’re told to keep quiet, because raising these concerns would be a gift to the Tory press; we’d just be helping to keep the heartless greedy bastards in government forever. And of course, no one wants to do that.

But does it really follow that our support for the Corbynistas has to be unconditional, our loyalty absolute? The Labour movement has been in the habit of depending on women’s (and other oppressed groups’) loyalty, reasoning that we have nowhere else to go. But that’s what’s so frustrating: women are not a minority, so why haven’t we created somewhere else to go? It’s noticeable, for instance, that more young women seem to have been galvanized by Corbyn’s campaign than have been inspired by the founding of a new Women’s Equality Party. So far, the WEP has looked pretty moderate and middle-of-the-road, but just as the Corbynistas have shaken up the Labour Party, so women joining the WEP en masse could redefine what it is about. It’s true that without proportional representation the WEP is doomed to remain electorally on the margins, but it could be to feminism what the Greens are to environmentalism (or what UKIP, unfortunately, is to racism)—a force that the mainstream parties must respond to in their own thinking and policymaking.

But I’m not really expecting that to happen. There has never been a feminist revolution: a revolution planned and led by women that put women’s interests front and centre. And there probably never will be, because not enough women would support it. Most women think it’s selfish and unfair to put their own interests ahead of men’s, and most still seem to believe that men are better equipped to lead. So we go on putting our faith in men, and we go on being surprised and disappointed when they do what we refuse to—put themselves first.