Debbie Cameron reads a book about the sexual politics of genetic science.

Sarah S. Richardson, Sex Itself: The Search for Male and Female in the Human Genome (University of Chicago Press, 2013)

The X and Y chromosomes, were discovered, respectively, in 1890 and 1905. Today we refer to them as the ‘sex chromosomes’, but that was not their original name. When the X was first identified, it was labelled the ‘odd’ or ‘accessory’ chromosome, because some sperm had it and others did not (later it would be recognized that what they had instead was the smaller Y). Initially it was unclear what purpose the X served, or even if it had a function at all: it certainly wasn’t obvious that it had anything to do with sex. At the turn of the 19th/20th century, scientists believed that the development of a fertilized egg into a male or a female organism was a long drawn-out process whose outcome depended on environmental factors such as temperature and nutrition.

The first scientist who did connect the X chromosome to sex suggested it was ‘the bearer of those qualities that pertain to the male organism’. A few years later, however, the Y chromosome was discovered, and researchers realized that, at least in the organisms they were studying, which were mainly insects and worms, sex depended on whether the X-bearing egg was fertilized by an X or a Y-bearing sperm. The XX combination produced females, the XY combination produced males. Further research showed that this pattern does not occur in every species. In birds, for instance, it is reversed, with males having two versions of the larger chromosome while females have one larger and one smaller one. There are also species like the mole vole which have no Y chromosome—males have XO (ie a single X) rather than XY. But the ‘female XX/male XY’ pattern was found to be typical of mammals, including humans.

The first scientist who did connect the X chromosome to sex suggested it was ‘the bearer of those qualities that pertain to the male organism’. A few years later, however, the Y chromosome was discovered, and researchers realized that, at least in the organisms they were studying, which were mainly insects and worms, sex depended on whether the X-bearing egg was fertilized by an X or a Y-bearing sperm. The XX combination produced females, the XY combination produced males. Further research showed that this pattern does not occur in every species. In birds, for instance, it is reversed, with males having two versions of the larger chromosome while females have one larger and one smaller one. There are also species like the mole vole which have no Y chromosome—males have XO (ie a single X) rather than XY. But the ‘female XX/male XY’ pattern was found to be typical of mammals, including humans.

With these discoveries, X and Y became not only ‘sex chromosomes’, but also sexed chromosomes: X was thought of as the ‘female’ chromosome (despite the fact that male mammals have one too), and Y as the ‘male’ chromosome. And with that presumption of male and femaleness, the X and Y chromosomes began to acquire the cultural baggage which is the subject of Sex Itself. Using a series of case studies, Sarah Richardson explores the way the study of sex and genetics has been shaped throughout its history by cultural beliefs about gender. The cases she considers include the (now discredited) theory that men with an extra Y chromosome are hyper-aggressive ‘supermales’, the question of whether women’s two Xs explain their greater susceptibility to autoimmune diseases, the debate on whether the Y chromosome is bound for extinction, and the claim that men and women are as different genetically as humans and chimpanzees. Individually and collectively these cases tell a story about the influence of gender ideologies on science, and conversely, about the role played by science in reproducing and legitimating those ideologies.

Chromosomes R Us?

A recurring theme in the story is the tendency for writers to ‘promote the X and Y as symbols of maleness and femaleness with which individuals are expected to identify, and in which they might take pride’ (p.4). This is particularly noticeable in men’s writing about the Y chromosome. In a book called Adam’s Curse, published in 2003, the geneticist Bryan Sykes rhapsodizes about what he refers to as ‘the bearer of my maleness and the token passed unaltered down from a long line of fathers’. He goes on:

I see it in my own father, as he leads his RAF squadron in the Second World War. I see it in my grandfather, fighting in the trenches and wounded in the battle of the Somme a generation earlier.

The ostensible subject here is biological maleness, but the rhetoric is all about masculinity. If Sykes’s father had been a chartered accountant and his grandfather had kept a ladies’ hat shop, they would still have had Y chromosomes; but Sykes’s invocation of them would not have conjured up quite the same picture of noble manliness.

Gender stereotyping is also a feature of writing about the X chromosome. In her 1999 book Woman: An Intimate Geography, the science writer Natalie Angier associates what she calls ‘the mystical X’ with ‘female intuition’, and accords a special meaning to female ‘mosaicism’. This poetic-sounding word is a technical term: it refers to the fact that XX women inherit one X from each parent, but in every cell one of the two Xs is ‘inactivated’ (its genes are ‘switched off’ and not ‘expressed’). Since the one that remains active may be either the maternal or paternal X, women are a ‘mosaic’ of different genetic influences. Or as Angier puts it, ‘a woman’s mind is truly a syncopated pulse of mother and father voices, each speaking through whichever X …happens to be active in a given brain cell’.

Gender stereotyping is also a feature of writing about the X chromosome. In her 1999 book Woman: An Intimate Geography, the science writer Natalie Angier associates what she calls ‘the mystical X’ with ‘female intuition’, and accords a special meaning to female ‘mosaicism’. This poetic-sounding word is a technical term: it refers to the fact that XX women inherit one X from each parent, but in every cell one of the two Xs is ‘inactivated’ (its genes are ‘switched off’ and not ‘expressed’). Since the one that remains active may be either the maternal or paternal X, women are a ‘mosaic’ of different genetic influences. Or as Angier puts it, ‘a woman’s mind is truly a syncopated pulse of mother and father voices, each speaking through whichever X …happens to be active in a given brain cell’.

Focusing on ‘mosaicism’ gets around the obvious problem with representing X as the ‘female’ chromosome when men have one too: the point that is emphasized is that women have active Xs from two different sources, whereas in men the X is always from the same source, their mother. Some commentators, especially male ones, are more explicit than Angier in using this idea to give pseudo-scientific substance to ancient and sexist notions of women’s nature as unpredictable, capricious and full of contradictions. Richardson quotes David Bainbridge’s 2003 book The X in Sex, which informs us that the female double X is ‘a natural reminder of just how deeply ingrained the mixed nature of women actually is…women are mixed creatures and men are not’.

‘Save the males!’

While the gendering of X and Y has been going on continuously since the early 20th century, its form has changed over time to reflect cultural shifts and new developments in gender politics. A striking example is the way recent debates about the Y chromosome have been influenced by the rise of ‘men’s rights’ politics since the 1990s. Bryan Sykes’s Adam’s Curse, mentioned earlier, belongs to a whole genre of books (others include Steve Jones’s Y: The Descent of Man and Peter McCallister’s Manthropology: the Science of Why the Modern Male is Not the Man He Used to Be), in which discussions of the nature, function and future of the Y chromosome become a vehicle for the expression of anxieties about the supposed decline in men’s status since the advent of second-wave feminism.

While the gendering of X and Y has been going on continuously since the early 20th century, its form has changed over time to reflect cultural shifts and new developments in gender politics. A striking example is the way recent debates about the Y chromosome have been influenced by the rise of ‘men’s rights’ politics since the 1990s. Bryan Sykes’s Adam’s Curse, mentioned earlier, belongs to a whole genre of books (others include Steve Jones’s Y: The Descent of Man and Peter McCallister’s Manthropology: the Science of Why the Modern Male is Not the Man He Used to Be), in which discussions of the nature, function and future of the Y chromosome become a vehicle for the expression of anxieties about the supposed decline in men’s status since the advent of second-wave feminism.

Richardson examines this controversy in a chapter called ‘Save the Males!’, a slogan which has been used by the geneticist David Page. Page was the first researcher to map the human Y chromosome, and he rejects the argument advanced by some other scientists that the Y is a ‘relic’, a ‘degenerate’ version of the X with very limited genetic value (it contains far fewer genes than the X, and many of them are inactive), and that as such it is destined to become extinct. In 2002, the Australian feminist geneticist Jennifer Graves speculated that the Y would disappear within 10 million years. Page responded by declaring his intention to ‘defend the honor of the Y chromosome in the face of a century of insults to its character and its future prospects’.

Graves was not suggesting that men would become extinct (which, since humans reproduce sexually, would imply the extinction of the entire species). Rather she predicted that a different sex-determining system would evolve in humans, just as it evidently did in species like the mole vole, which has no Y chromosome. But Page was quick to cast supporters of her theory as feminists animated by anti-male prejudice. ‘The idea of the Y as a shiftless, no-good degenerate chromosome’, he said, ‘is entirely too appealing and attractive to resist, for reasons that have little to do with science and lots to do with sexual politics’. His own language invites the same criticism: since a microscopic piece of genetic material does not have a ‘character’ to be ‘insulted’, it is obviously men’s honour that Page feels impelled to defend, and that too has more to do with sexual politics than with science. But as Richardson observes, it is Graves rather than Page who is charged with importing a political agenda into science, and called on to respond to accusations of ‘bias’.

Science and politics

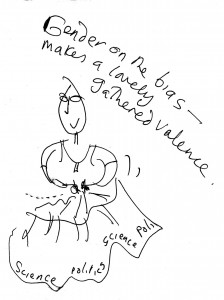

On the question of political agendas in science, Sarah Richardson’s own views are complicated. She reserves the term ‘gender bias’ for cases where gendered assumptions and prejudices operate covertly and without acknowledgment, as they did for instance in 1960s discussions of the XYY genotype . The recent debate about the Y chromosome exemplifies a more overt political stance-taking which Richardson prefers to call ‘gender valence’. The ‘bias’/‘valence’ distinction is part of an argument which starts from the position that there is no such thing as an ‘unbiased’ science, if by that we mean a science without any cultural preconceptions. Although science takes nature as its object of study, it is itself a product of culture, and its practitioners are social beings: they are inevitably influenced by their life experiences, beliefs and political interests. Rather than denying this, Richardson suggests that scientists should make their ‘valences’ explicit. She argues that political commitments need not detract from the quality of science; they may even help to improve it, by encouraging radical challenges to established orthodoxy.

On the question of political agendas in science, Sarah Richardson’s own views are complicated. She reserves the term ‘gender bias’ for cases where gendered assumptions and prejudices operate covertly and without acknowledgment, as they did for instance in 1960s discussions of the XYY genotype . The recent debate about the Y chromosome exemplifies a more overt political stance-taking which Richardson prefers to call ‘gender valence’. The ‘bias’/‘valence’ distinction is part of an argument which starts from the position that there is no such thing as an ‘unbiased’ science, if by that we mean a science without any cultural preconceptions. Although science takes nature as its object of study, it is itself a product of culture, and its practitioners are social beings: they are inevitably influenced by their life experiences, beliefs and political interests. Rather than denying this, Richardson suggests that scientists should make their ‘valences’ explicit. She argues that political commitments need not detract from the quality of science; they may even help to improve it, by encouraging radical challenges to established orthodoxy.

In the 1990s, for instance, gay/lesbian and intersex activists challenged scientific claims they found politically objectionable, and campaigners protested against the use of genetic sex-testing to verify that female athletes were ‘really’ women. In the course of these controversies it became clear that there were real gaps in scientists’ knowledge. The research that was carried out to deal with this problem eventually led to a major advance in scientists’ understanding of genetic sex determination. Whereas the previous orthodoxy had held that sex was ultimately controlled by a single ‘master gene’, the new account posited a more complex ‘cascade’ model, in which sex is produced by a number of different genes interacting in particular ways at specific stages of development. Not all the relevant genes are on the so-called ‘sex chromosomes’—a finding which makes that always problematic label appear more questionable than ever.

Gender and the genome

The new approach to sex determination is one recent advance in knowledge that Sarah Richardson evaluates positively. But she concludes Sex Itself by drawing attention to the continuing presence of sexism in the science of ‘the post-genomic age’ (ie after the sequencing of the human genome). Echoing points made by Stephen Jay Gould in The Mismeasure of Man, a classic critique of biological racism, she comments that

the history of attempts to establish the biological essence of sex difference and the physical and mental inferiority of women follows a similar trajectory. Each time a new research program emerges, the claim is made that at last the difference between the sexes can be located, measured and quantified, and that the differences…are greater than ever previously imagined (225).

Genomics is the latest in a long line of research paradigms which have made that claim, but for many commentators, including Richardson, it isn’t just another step on the long and winding road, it is a revolutionary development with far-reaching social and political implications:

Genomics is transforming social relations. It is remaking categories of identity—concepts such as ‘blood relations’, racial or geographic ancestry, citizenship, and subjectivity—as well as notions such as what it is to be normal and healthy, what rights we have to privacy and to healthcare, and what responsibilities we have to others to maintain and pursue information about our health (216).

For feminists, it is therefore both important and urgent to challenge the old sexist assumptions that continue to inform this new scientific project.

One of the main areas in which genomic research could have significant consequences for women is medicine. Women’s health activists have long argued that it does not serve women’s interests when medical research treats men’s biology as the human norm. Some organizations have campaigned for more research on sex differences, and for the development of sex-specific treatments for common conditions like cardiovascular disease and depression. For me, this has always been quite a convincing argument: though I regard most sex difference research as worthless garbage, I have generally made an exception for studies whose findings might have clinical applications. But Richardson has taken a close look at some studies of this type, and her criticisms of them are pretty damning.

First, almost all the studies Richardson reviewed conflated the effects of sex with those of gender: often they attributed differences to biological factors without considering the possibility that they might be linked to social conditions or norms that lead men and women to behave differently, in ways that affect their bodies and their health. A classic if somewhat trivial example is the finding that men who wear contact lenses suffer more frequently than women from a particular form of eye irritation. This could hypothetically be because genetic differences make males being more susceptible to the condition; but the actual explanation is that women tend to be more careful about cleaning their lenses properly.

First, almost all the studies Richardson reviewed conflated the effects of sex with those of gender: often they attributed differences to biological factors without considering the possibility that they might be linked to social conditions or norms that lead men and women to behave differently, in ways that affect their bodies and their health. A classic if somewhat trivial example is the finding that men who wear contact lenses suffer more frequently than women from a particular form of eye irritation. This could hypothetically be because genetic differences make males being more susceptible to the condition; but the actual explanation is that women tend to be more careful about cleaning their lenses properly.

Second, Richardson found that studies tended to overgeneralize about ‘men’ and ‘women’, ignoring the variation that exists within each group. Calculations that flatten out not only the differences between individuals, but also those between sub-groups like men and women of different ages (age has biological consequences too), mean that sex-difference scientists end up talking about the difference between Mr and Mrs Average, a mythical couple who may bear little resemblance to any actual person.

Finally, the studies Richardson reviewed were generally more attentive to differences between men and women than to cases of similarity and overlap. This is a much discussed problem with all kinds of sex difference research: the assumption is that if you find a difference that is a ‘positive’ result, and if you don’t your study is a failure. That assumption can lead researchers to overemphasize the importance of whatever differences they do find. In medical research this is a particular concern, since ‘there are risks to women’s health if sex differences are exaggerated’ (p.223). Richardson also mentions the potential distorting effect of the profit motive: since there is money to be made from the development of new, sex-specific therapies, some players in this area (eg drug companies who fund research) have a financial interest in ‘talking up’ findings of difference.

I still think there is a feminist argument in favour of sex-difference research for medical purposes, but Richardson’s survey makes clear that it needs to be designed a lot more carefully, and interpreted a lot more critically, if it is to serve the interests of women rather than those of ambitious research scientists and the pharmaceutical industry.

Postscript: some thoughts about feminists and science

Science is a relatively neglected subject in T&S. The archive does contain a few pieces dealing with scientific topics like reproductive technology, sex-testing in sport and evolutionary psychology; more recently we’ve published a review of two books by feminists criticizing ‘brain sex’ research. But overall it would be fair to say that our coverage of science has been pretty sparse.

I find this both strange and somewhat worrying, because I don’t think anyone could deny the importance of science in the 21st century world, nor its relevance to the concerns of feminists. Science is the arena in which some key ideological battles—about the nature and extent of sex differences, about sexuality, about reproduction and mothering, about the causes of violence and crime—are fought; to intervene effectively in these debates, it is useful for feminists to understand the science they criticize. That understanding is also needed to assess the practical applications of scientific knowledge and their probable consequences for women. If feminists want science to be used in a way that serves women’s interests, and to hold it to account when it does not, we need to inform ourselves about what scientists are doing.

The new genomics is an area of science that has both ideological and practical implications: reading Sarah Richardson’s account made me wonder why feminists aren’t discussing it more outside academic/scientific circles. That got me thinking about the more general question of feminist attitudes to science. Although I am generalizing here, and there are obviously exceptions, it does seem to me that we have not engaged with the politics of science in the same way we have engaged with, say, the politics of culture. We don’t generally assume that you need a PhD to produce a feminist analysis of art, language, literature, music, film, TV or fashion; but when it comes to science, many of us who are not scientists seem to think our lack of specialist knowledge makes it impossible for us to understand the issues, and we should therefore leave discussing them to the experts.

Of course there will be differences in the way issues are understood by people with and without expert knowledge: that is true about all subjects, not just science. But the perception that some issues are just impossible for non-specialists to understand at any level is something you might expect feminists to be critical of, since it’s always been an argument used by the powerful—the medical establishment, for instance—to block challenges to their authority. It’s also, frankly, nonsense: it always amazes me when women who will happily discuss the latest developments in feminist and queer theory, or who spent their youth poring over the impenetrable works of Lacan, Derrida and Foucault, say that subjects like genetics and neuroscience are beyond their comprehension.

Of course there will be differences in the way issues are understood by people with and without expert knowledge: that is true about all subjects, not just science. But the perception that some issues are just impossible for non-specialists to understand at any level is something you might expect feminists to be critical of, since it’s always been an argument used by the powerful—the medical establishment, for instance—to block challenges to their authority. It’s also, frankly, nonsense: it always amazes me when women who will happily discuss the latest developments in feminist and queer theory, or who spent their youth poring over the impenetrable works of Lacan, Derrida and Foucault, say that subjects like genetics and neuroscience are beyond their comprehension.

I can’t help wondering if the representation of science as somehow more inaccessible than other subjects (even very abstruse ones like queer theory) reflects the internalization, even among feminists, of the idea that science is a men’s thing, uncongenial to most women’s interests or, worse, beyond their intellectual grasp. That was certainly the attitude when I was growing up. Although I went to an all girls’ school which emphasized academic achievement, only girls who wanted to become doctors (which was considered OK because it’s a ‘helping profession’) were expected to study maths or physics or chemistry. That’s why I took only one science subject, and only up to O level; it’s also why that subject was biology, which at the time was considered easier than the others, as well as more relevant to girls’ interests. It was the science you could study (at a basic level, anyway) without ruining your femininity. In a further demonstration of my feminine credentials, I only managed a mediocre grade 3.

For the non-scientist, it does take some intellectual effort to read an academic science book like Sex Itself. There were parts of it which I found difficult to follow (it would have benefited from a glossary of technical terms, from ‘allele’ to ‘zygote’), and I’m sure there are points of detail I haven’t grasped. But in the area of science there’s a real problem with relying on more ‘accessible’ sources. Media coverage tends to be simplistic and sensationalizing; as for popular science books, you only have to look at the passages I quoted earlier from Adam’s Curse and Woman: An Intimate Geography to see why Sarah Richardson identifies them as part of the problem her book is about.

For the non-scientist, it does take some intellectual effort to read an academic science book like Sex Itself. There were parts of it which I found difficult to follow (it would have benefited from a glossary of technical terms, from ‘allele’ to ‘zygote’), and I’m sure there are points of detail I haven’t grasped. But in the area of science there’s a real problem with relying on more ‘accessible’ sources. Media coverage tends to be simplistic and sensationalizing; as for popular science books, you only have to look at the passages I quoted earlier from Adam’s Curse and Woman: An Intimate Geography to see why Sarah Richardson identifies them as part of the problem her book is about.

For me, reading Sex Itself was worth the effort. It was sometimes quite challenging, but I never found it boring. Most importantly, it has made me a lot better informed about recent developments in genetic science, and given me a better understanding of what’s at stake in those developments for feminists.

Cartoons by Angela Martin © Angela Martin 2014

a ereally useful review of a really useful book – going to read it. and funny, too. interesting that cameron reviews the book, herself and ‘trouble and strife’ while she is at it.

Pingback: Whatever You do I can do… Apparently not | randolphriot