Not the revolution…but not the end of the world 2

Britain has got its second woman Prime Minister–and once again, she’s a Conservative. You wouldn’t expect feminists to be hailing this result as a triumph, but why, asks Debbie Cameron, are so many of them proclaiming it a disaster?

The first article I saw was in the New Statesman, and I thought: ‘well yes, of course’.

The second was in the Guardian. I thought, ‘right’.

The third was in the (Scottish) National. I thought, ‘OK, but this is getting a bit repetitive’.

Then three more popped up in my feed in quick succession, from various news and comment websites. I thought, ‘hang on a minute, what is this?’

If you’re wondering what I’m talking about, the answer is, opinion pieces dealing with the battle between two women for the Tory leadership. Opinion pieces written by women, and summarized in headlines like these:

A leadership contest between two women is not a feminist revolution.

Don’t confuse the Conservatives’ embrace of women leaders with feminism.

Sub-prime: is May vs Leadsom good for feminism? (spoiler: no it fucking well isn’t)

May or Leadsom? Either way, our next PM will be a disaster for feminism.

This contest is, of course, old news: I’d barely started to write about it when Andrea Leadsom announced she was withdrawing and leaving the field to Theresa May. But that doesn’t mean there’s nothing left to discuss. The point commentators were making when it was May v. Leadsom is still being made now it’s just May; it would be made about any woman who aspired to lead the Conservative Party, and probably about many who might aspire to lead other parties. And I want to explain why I think that’s a problem.

No, it’s not a feminist revolution–but who said it was?

I don’t disagree with the (obvious) point that these women’s political views are antithetical to the principles of feminism. Leadsom is a free-market zealot and a social conservative who bangs on about God and family values. May is less of an ideologue, but at the Home Office she has taken a hard authoritarian line on human rights, immigration and security. She has now, as PM-elect, laid out a programme which surprised me by looking much less right-wing than I’d have imagined, but I’m not really expecting her administration to be any better for women than the Conservative-led governments we’ve had since 2010. It could well be worse, if there’s a post-Brexit economic meltdown and her response is to initiate a new round of slash-and-burn austerity measures. If that happens it will be women (as the majority of part-time and low-paid workers, public sector employees, single parents, carers and, of course, users of specialist women’s services which have already been cut to the bone) who will suffer most.

So, there’s no way I’m going to confuse the Tories’ willingness to make Theresa May their next Prime Minister with a feminist revolution. But I still think there’s something a bit odd about this stream of finger-wagging articles telling me not to.

Several of the authors begin by implying that when they criticize May and Leadsom they are departing from some kind of feminist orthodoxy. In her New Statesman piece, for instance, Laurie Penny writes:

I have spent the day being informed that I should be pleased that the future leader of my country will be female.

Really, Laurie? By whom? You’re a prominent social justice warrior who works for a left-wing magazine, so where did you encounter all these cheerleaders for May and Leadsom?

Then there’s Kate Pasola in The Skinny, who has somehow been made to feel that the right response to an all-female Prime Ministerial contest would involve

doing handstands on the back of a motorbike, braless, wasted and screaming for joy.

Where, I wonder, did she get that idea?

By the time I’d read four variations on this theme, I was starting to think I must have missed a whole other set of articles by feminists making the argument Penny and Pasola criticize—that the Tory contest was a triumph for feminism. So I started to search through the coverage more systematically. What I found was a further crop of pieces just like the ones I’d already read (i.e., ‘stop telling me this is good for feminism because it isn’t’) and not a single piece making the opposite argument from a feminist perspective. I did find one piece by a Tory who said the contest was a triumph for women, but the point was that the rise of May and Leadsom showed that feminism wasn’t necessary: women could succeed on their own merits without the special treatment feminists were always demanding.

So, if anyone actually had confused the Tory leadership contest with a feminist revolution, I didn’t find the incriminating evidence. Instead I found myself asking what had prompted so many emphatic refutations of an argument no one, and certainly no feminist, seemed to have made.

And that wasn’t my only question.

‘The inevitable barrage of misogyny’

I take it for granted that no one with a serious feminist political analysis could be anything but deeply unhappy with a right-wing Conservative government. But that was always what we were going to get after the referendum: the Tories won the 2015 General Election, and if the nation had voted to stay in the EU we’d have been stuck with David Cameron till 2020. When the result turned out to be Leave and Cameron resigned, the general expectation was that we’d be getting Boris Johnson instead. Replacing, in other words, one smirking, self-serving Old Etonian with another who would follow much the same path.

Then when Johnson withdrew it looked as if we might get the guy who stabbed him in the back, Michael Gove—not an Old Etonian, but a fully paid-up member of the swivel-eyed loon tendency. However, Gove’s behaviour towards Johnson turned out to be too much even for his fellow-loons. So May became the ‘continuity’, ‘safe pair of hands’ candidate and Leadsom stepped into the vacant loon slot.

In the event of a leadership election someone was always going to fill those positions. The fact that they were both filled by women wasn’t the result of any conspiracy to make the Tories look like feminists. It was more of an improvised solution to the unforeseen problem of men going seriously off-piste. But what the writers of these endless ‘it’s a disaster for feminism’ pieces seem to be saying is that they’d rather things had gone according to plan, and that we’d ended up with another male PM. That Johnson or Gove would not have been as bad for feminism, or for the majority of women, as May or Leadsom.

The thinking behind this comes closest to being made explicit by Kate Pasola:

Intersectional feminism gains nothing from a female prime minister when the options are May and Leadsom. I’m dreading their policies and their attitudes, as I would with any right-wing leader. But I’m also dreading the inevitable barrage of misogyny these women will endure. I’m dreading their inevitable legacies as iron women and witches; for their evil actions to be tethered arbitrarily to their gender. I’m not excited for a woman to be given the power to represent my gender, only to see it go to sore, heartbreaking waste.

She’s saying that these right-wing women will be judged as representatives of their sex, and that their actions will be presented in specifically gendered terms; like Margaret Thatcher before them, they’ll be remembered as iron ladies and evil witches. And she correctly identifies the reason: misogyny. But by writing a piece about how terrible the two women are and how much she wishes they had not been chosen, she is arguably repeating the very gesture she claims to deplore. Adding, in effect, to the ‘barrage of misogyny’.

Of course I’m not suggesting feminists shouldn’t criticize Tory women; but why can’t we do it ‘as we would with any [male] right-wing leader’, on the basis of their beliefs and words and actions? As feminists, should we not also be critical of the double standard which makes it OK to judge women as more evil than men who think/say/do exactly the same things?

Just before the bit I’ve already quoted from her article, Kate Pasola mentions a friend of hers asking ‘is this what Emily Davison threw herself under the King’s horse for?’ Rhetorically, this is obviously a question expecting the answer ‘no’. But actually I think the true answer must be ‘yes’. Suffragettes like Davison believed that women’s enfranchisement was desirable in and of itself. They demanded political rights for women without attaching conditions. There was no, ‘so long as they’ve got the right politics and vote in the approved manner’.

Some socialists did fear that giving women the vote would only help the Conservative Party, and for several decades it was in fact the case that the Tories benefited most. But would any contemporary feminist seriously suggest that suffrage was therefore bad for women and ‘a disaster for feminism’? It’s one thing to say that equal rights are insufficient (which second wave feminists did say, loudly), and another to say they are unnecessary or irrelevant.

Maybe this has some bearing on a question broached by numerous commentators on the May/Leadsom contest, including Eve Livingstone in the Guardian:

Much has been made of the fact that, for all its talk of feminism and equality, the left has returned a grand total of zero female prime ministers, in comparison to what will become the Conservatives’ two. … What is the secret to [the Tories’] success? Is it a strong commitment from leadership to equal representation? A particularly good mentoring and coaching initiative? Positive action strategies?

Obviously not, but the answer Livingstone eventually arrives at does not really get to the heart of the matter.

In a country so entrenched in inequality, it’s no coincidence that our female leaders have come from the right with an inherently sexist ideology of individualism and meritocracy. It’s that very inequality that ensures the system doesn’t fit women leaders of any other ilk.

This seems to miss the point that male dominance is entrenched on the left as well as the right: it’s not just ‘the system’ that keeps women out, it’s the actions of men defending their own interests. I do think she is right to point to the ideology of individualism and meritocracy as a factor which makes things slightly easier for a small number of right-wing women. A woman leader who presents herself as an individual exception to the male norm, and who does not demand equality for women as a group, is not a threat to men’s collective power; they know her ascendancy will only be a temporary blip, after which normal service will resume. So they can afford to be relaxed about the occasional female leader–especially if she steps into the breach when the party is divided or the country is in crisis (May will be dealing with both those situations).

But I think there are other reasons why female leaders have been more acceptable on the right than the left. One has to do with the ingrained cultural misogyny alluded to by Kate Pasola—the tendency to put powerful women in sex-specific boxes with labels like ‘overbearing mother’, ‘strict nanny’, ‘headmistress’, ‘Iron Lady’, ‘wicked witch’. These archetypes have currency across the political spectrum: they don’t belong exclusively to either the right or the left. But on the right some of them can sometimes be made to work to a female leader’s advantage.

This is because the right attracts authoritarians, people who respond positively to firmness and discipline. Not all of them like being told what to do by a woman, but they do at least find archetypal female authority figures like Mummy and Nanny familiar and understandable. For some men women’s firmness is comforting, for others it may even be a turn-on—think of Mitterand’s description of Thatcher as having ‘the eyes of Caligula and the mouth of Marilyn Monroe’, or the fetish that’s been made of Theresa May’s shoes (notice that the cartoon I’ve reproduced comes from a pro-Tory paper: the ‘female leader as dominatrix’ idea isn’t only used by political opponents to delegitimize women, it can also be deployed by their admirers). And precisely because they aren’t feminists, right-wing women have fewer scruples about exploiting their femininity by playing up to these traditional sexist stereotypes.

On the left, by contrast, which is ideologically anti-authoritarian, the traditional female authority figures have little or no appeal. In addition, most left-wing women don’t want to play Mummy or the Iron Lady. They’d rather downplay their femininity than exploit it: they believe they should be treated as men’s comrades and their equals. In practice, however, they often find out the hard way that however they behave, their sex affects the way they’re perceived. They get stereotyped (and then resented) by default, because there are no alternative, widely intelligible models of female (or gender-neutral) political leadership.

Purity politics?

Another thing that helps to maintain male dominance on the left is the kind of feminist purity politics exemplified by the articles I began with. The sentiment they express could be glossed as ‘If we can’t have a woman leader who perfectly represents all our political ideals, we’d rather not have one at all. No compromise, sisters! If she isn’t going to lead us to the Promised Land where all oppressions melt away, then she’s an enemy of true feminism and our policy must be zero tolerance’.

Some of this may be virtue-signalling, and some of it may be about expecting more from women than we do from men, and therefore being more critical of women who fall short. But I don’t think those things are the whole story. Feminist ambivalence about female leadership goes back a long way.

The second wave Women’s Liberation Movement was self-consciously egalitarian and anti-hierarchical, rejecting the idea that feminist groups should have leaders or spokeswomen. Individual women who were seen or publicly treated as movement leaders, whether or not they had actually sought that status for themselves, were often subjected to harsh criticism. In the context of feminist activism the rejection of hierarchy makes sense (even if it has sometimes been taken to overzealous extremes). But it is counter-productive to carry the same attitude over into the context of mainstream party politics. If you’re working within a hierarchically-structured organization, the only thing you’ll achieve by refusing to compromise on your vision of the ideal feminist leader is an endless succession of male leaders.

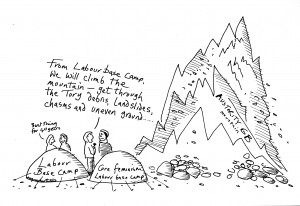

But there are now feminists who seem to believe that it’s irrelevant, or even crassly reactionary, to care whether women are represented in leadership positions. The Labour MP Jess Phillips has been attacked by supporters of Jeremy Corbyn for suggesting that her Party’s continuing preference for male leaders is a symptom of its continuing sexism. Some of her critics have said explicitly that Corbyn is a better feminist than any of the available women: it’s the politics that matter, not the sex of the individual who promotes them. Similarly, across the Atlantic, some of Bernie Sanders’s supporters insist that he will do more to advance the feminist cause than Hillary Clinton.

At the centre of this argument is a serious point: that the interests of highly privileged women should not take priority over those of the poorest and most oppressed, or indeed the great majority of less privileged women. Few feminists would disagree with that. If some decided, on that basis, to vote for Sanders rather than Clinton (or Corbyn rather than Eagle), I can understand their reasoning. What bothers me is when feminist women go from saying: ‘given the choice between these two individuals I’m afraid I’ll have to go for the man’ to ‘it really shouldn’t matter to a feminist whether a leader is male or female: the question is whether he or she has the right policies’.

Invariably this is said by a woman who is defending her support for a particular male politician, a Sanders or a Corbyn. But when it’s elevated to a general principle, I think it points to the difficulty we still have in visualising women leaders who aren’t just clones of the ones we’ve already found wanting, like Thatcher and Clinton. Why do we think women leaders can only ever represent the narrow interests of the group they belong to (typically white middle-class professional women), when male politicians—usually also white and from an elite class—are credited with the ability to go beyond that? Why can’t we imagine a female socialist leader, or a working class feminist leader? Maybe the answer has something to do with the fact that we’ve never had one. But if so, isn’t that a serious flaw in the argument that it doesn’t matter who a leader is, only what his or her policies are?

Oddly enough, you don’t hear feminists making that argument about anything else. No one says ‘it doesn’t matter whether women become scientists so long as the men are doing the right kind of science’. Or ‘it doesn’t matter if there are no women on the Booker Prize shortlist so long as the men’s books present women sympathetically’. On those subjects the feminist refrain is ‘you can’t be what you can’t see’. Girls need to know that science or literature isn’t just a male preserve, and to really know that, to internalize the truth of it, they need to see women doing science, or writing critically-acclaimed novels.

Political leadership is no different. If we are ever to have women leaders of the kind we really want, the kind we could not just dutifully support but actually be inspired by, we need future generations to see female leadership as normal and unremarkable. And for that to happen, we need to recognize that the female leaders we don’t like or agree with have as much right to be where they are as their male equivalents. They may be no better, but they’re also no worse. We don’t have to like them, make common cause with them, or refrain from criticising their shitty politics. But nor do we have to condone—still less join in with—the chorus of everyday misogyny. We can point out that the elevation of Theresa May is not a feminist revolution without suggesting it’s the end of the world.