Margaret Thatcher was as divisive in death as she had been in life: when she died earlier this month there were outpourings of adulation from her admirers, while some of her detractors held protests and parties. Her status as Britain’s first woman prime minister was constantly emphasized, whether in positive terms or negative ones. Here, four contributors reflect on their experiences of the Thatcher years, their feelings about Thatcher and what her career might mean for women and feminists today.

I WOUDN’T HAVE MISSED IT FOR THE WORLD

Emma Wallace remembers her involvement in Women Against Pit Closures during the miners’ strike

I was born in 1965 and lived until I was eighteen in a village to the east of Rotherham. There were five collieries within a five-mile radius, and a high proportion of men who lived in the village were employed within the coal industry.

For me the most important event of the 1980s was the 1984-5 miners’ strike. When it broke, I was eighteen years old and had been living in Sheffield for several months. Unemployment was already high in south Yorkshire owing to lay-offs in the steel industry, and being unemployed myself I felt that we all had to fight together to prevent the situation getting any worse. My mother was of the same opinion, so we both went to join the Sheffield Women Against Pit Closures group.

I had never been involved with any political organisation or pressure group before I joined WAPC and I was very impressed with the organisation, as it was highly democratic; we all joined in the decisions, and we all took part in activities to support the strike. There were women in the group from all walks of life with differing viewpoints, perspectives and experiences, and it was wonderful how we all managed to get along with only minor disagreements.

The major function of SWAPC was to fund-raise. We also used to go on demonstrations and arrange pickets, and it was these events more than anything else which affected me, as they opened my eyes to many things which I didn’t realise happened in this country.

Before the strike I had always been of the opinion that we had a fair, just and neutral police force. However, as the dispute progressed I began to realise that this simply wasn’t the case. The police were just as violent towards us as women as they were to the men, but in addition they used to treat us with a mixture of contempt and sexual intimidation. The comment was always made that no woman worked down the pit, so we shouldn’t be on the picket line but at home doing the dishes, or in bed with our husbands. They were often obscene, and frequently talked to us like dirt. In the end I grew to accept this, viewing it as part of the job. The only thing that really worried me was the thought of being arrested whilst I was having a period. I’d heard the police tactic with women was to arrest them and not let them go to the loo, and I felt that being degraded in that way would be more than I could take.

The police tactics at the big pickets were really frightening. One night two of us went to Treeton. There were no police when we got there, but they soon arrived in great numbers. They came in from both sides of the village so, being in effect surrounded, we fled in the only direction we couldn’t see blue flashing lights. I somehow ended up in the middle of a field, alone, not knowing where I was. Then the police searchlights began panning out from behind me and I was on the verge of panic. Over to my left was a small ridge, so I made my way to the bottom and then climbed up. As we looked down we saw blue flashing lights and riot shields everywhere. Because of the searchlights we had to lie flat for the best part of three hours before we dared attempt to leave the village. We got out via railway lines, back gardens, and with a lot of dodging police cars in between. It was an incredible night which could have come straight out of a war film, but it happened less than ten miles from the centre of Sheffield.

Trying to explain what it was like to people who weren’t active in the strike was very difficult because most of the time I wasn’t believed. The TV and press were pouring out endless streams of rubbish, yet apparently they had more credibility than I did. Looking back on it now, I can’t help thinking that if I had been a man in, say, his mid-thirties, rather than an eighteen-year-old woman, people might not have been so dismissive.

After witnessing events such as Orgreave, where thousands of police in full riot gear with horses, dogs and armoured vans, fought with unarmed miners who were trying to picket the coke-works, I began to question our society and the assertion that Britain is a free country. In SWAPC there were women from Greenham Common, and women who had contacts in the Black community and Northern Ireland. After I listened to what they had to say, it began to appear to me that only people who supported the status quo were free; anyone who challenged the status quo, or even questioned it, had the powers of the state brought to bear on them. This idea made me feel uncomfortable, but there can never be a return to my pre-strike viewpoint. I know many women who were involved in the strike share that feeling, because for most of us it was the first time we had ever challenged the state.

The strike ended in March 1985. I went on the march back at Silverwood colliery, on a cold damp morning that I don’t think I’ll ever forget. Despite the fact that the strike was lost, I wouldn’t have missed that year for the world, and I’d do it all again tomorrow. I learned so much – about politics, about the country I thought I knew but found I had to come to terms with all over again, about people, about myself and about comradeship. The women at SWAPC had been like an extended family. We’d laughed together, cried together, been tired together and in danger together. We’d all experienced so many different things, but for me that was the spirit of the strike – comradeship.

This is an edited extract from a piece that originally appeared in Surviving the Blues, ed. Joan Scanlon (Virago).

EVERY WOMAN FOR HERSELF

As she joins the protestors gathered in Trafalgar Square, Atiha Sen Gupta ponders Margaret Thatcher’s legacy, and concludes that she is more alive than ever

I had been toying with the idea of going to Trafalgar Square. The idea of gathering in the Square on the Saturday after Margaret Thatcher’s death was conjured up by the Anarchist Collective 24 years ago. I had seen tatty stickers bearing this message pegged to adverts along tube escalators years before her passing. But then again, she was a human being, some counselled: was it wrong to go?

Liberal sensitivities aside, I went to the Trafalgar Square gathering to mark the death of Margaret Thatcher. It was cold. It was raining. I looked up at the sky and thought ‘Et tu, Brute?’ I started to feel that even the clouds were conspiring against us. Was it not enough that £8 million of public funds was going to finance this woman’s ‘ceremonial’ funeral? Was it not enough that the police were threatening to pre-emptively arrest people who wanted to protest her stately departure? However, according to estimates by the press, 3,000 protestors were in attendance. There were 1,700 police officers present. My maths isn’t great but that’s roughly one police officer to every two protestors. I’m flattered.

Seeing so many people out on such a hostile night was comforting. The right-wing media reports of the disgusting antics of left-wingers in rejoicing at her death state the facts but draw no conclusions from it. What does it say that so many people come out to ‘celebrate’ the death of an old woman? Does it say that the British public is fundamentally nasty? No. If John Major died tomorrow, I am willing to bet money that nobody would be out dancing in the streets. There’d be articles in the press condemning or elevating him but the public reaction would be wholly different and altogether more ‘respectful’. The gloating reaction to her death says more about Thatcher and her style of politics than it does about sections of the British public.

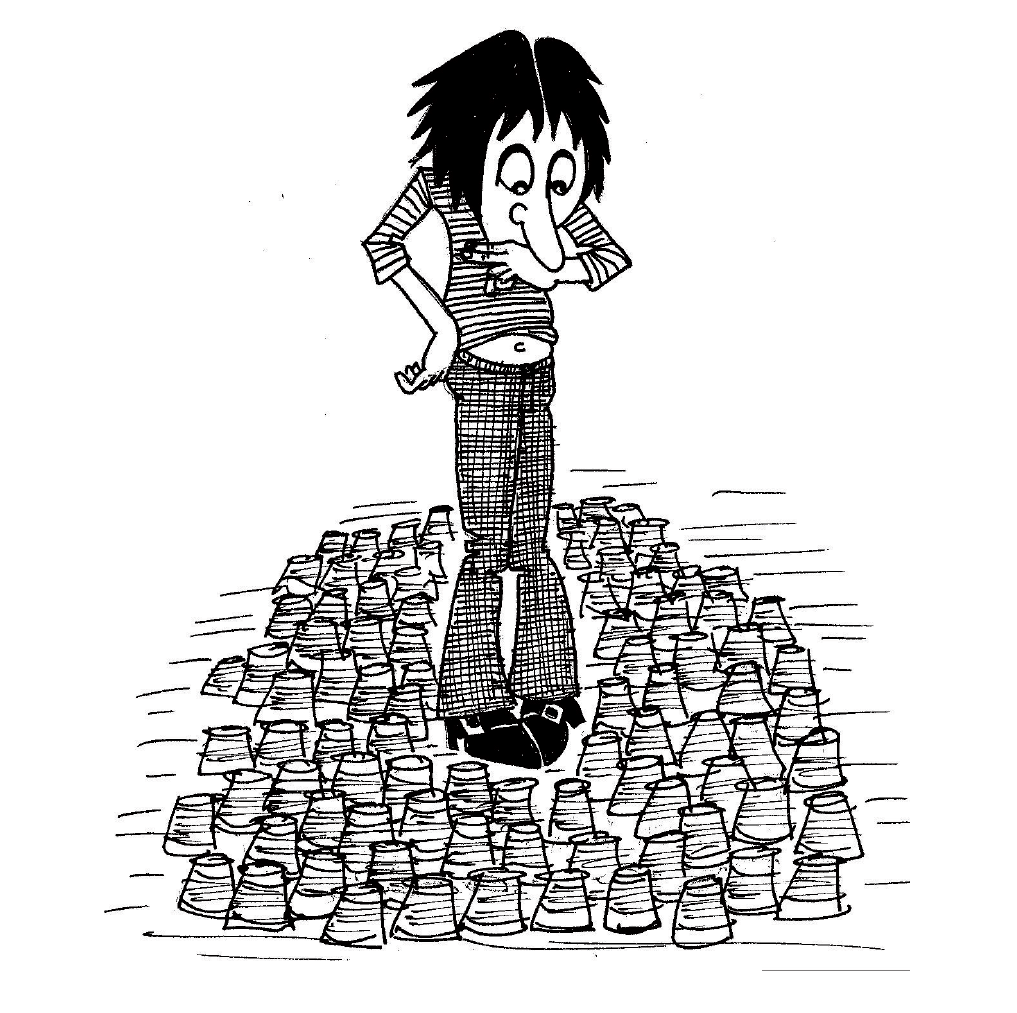

When I arrived, the police had encircled the Square in the hope that the revelry wouldn’t spill out of it. But there wasn’t much revelry. There were women, there were men, there were punks, there were drunks, there were teachers, there were students. There were the miners from 1984 bearing a banner from the North-East who appeared like celebrities. People were shaking their hands and having their photos taken with them. I marvelled at the creativity of the left when across the square I caught sight of a wonderful effigy of Margaret Thatcher made out of plumbing pipes, polystyrene and papier maché. She drifted regally across the crowd with square handbag in hand. Cleverly, her makers had her clutch a pint of semi-skimmed milk. Her hair was made up of bright orange Sainsbury’s bags which filled with wind like the sails on a ship and lit up the grey, drab square.

photo by Atiha Sen Gupta

The much-repeated and tedious idea that Thatcher was a woman and was therefore a fantastic role model for women is a nonsense – often propagated by men, who have no time for feminism or, by women, who have no time for feminism – do you see a pattern emerging? These anti-feminists (for generosity’s sake, let’s call them ‘non-feminists’) emphatically inform you that Thatcher was in fact a woman and that you should at least respect her for that. This ‘you’ refers to me. I have been involved in two virtual Facebook fights stemming from her death last Monday. The first was particularly nasty. A (female) friend on Facebook had written a eulogising tribute to the great ‘Mrs T’. I waded into the stream of comments and put my opinion down on the screen. One young woman had written that Thatcher dying was nothing to mourn. The reaction was hysterical. I then stepped in to support her and the elitist firing squad turned on me. The internet can be a lonely place. I was called a ‘knob’ for supporting the first anti-Thatcher woman (who was labelled ‘knob 1’). As I took over the anti-Thatcher position, I was labelled ‘knob 2’ which made me despair a little a bit. If you’re going to insult me, at least let me come first in something.

It has shocked me to note how many of my virtual friends (many of whom are women and/or from ethnic minorities) have seen Thatcher’s death as something to mourn – posting non-ironic tributes to her or liking others who have done so. This to me reflects the post-modern universe ushered into existence (to some extent by Thatcher) where nothing is fixed, identity is what you make of it and you can be what you want to be. So what if you’re black and you support Thatcher? That’s your free choice and nobody should pick you up on it. It is hard to speak hypothetically, but I doubt that these university-educated individuals (often with degrees in political science) would have mourned the likes of Thatcher 30 years ago. It wouldn’t have been fashionable. Students are supposed to be radical. If you’re 19 and a Tory where do you have left to go?

People who emphasise the uniqueness of her position as the first and, to date, only woman Prime Minister point out what she did do as a woman (i.e. managing to reach such a high level of office) rather than what she did not do (i.e. bringing women’s issues to the fore to enact societal change). Perhaps she cannot be blamed for this, in that her inaction on women’s struggles was consistent with her overall logic. There was, after all, no such thing as society. There were only individuals who were responsible for their own triumphs or tribulations. In her framework, she was a woman, she had made it and now it was up to other women to make it for themselves (or not). This overbearing individualism marked her time in power, but imagine how much she could have done had she understood feminism, social dynamics and oppression. She could have introduced more women to the Cabinet, she could have funded childcare for women who work, she could have criminalised rape in marriage. Should I go on?

photo by Atiha Sen Gupta

Margaret Thatcher was a capitalist first, and a woman second. She was the Jesus Christ of market capitalism. She pulled her socks up and got on with it so that everyone else could. She scraped and saved and succeeded to give us eternal life (on the stock market). Her legacy is everywhere – in the truisms we repeat to ourselves and to others in daily conversation, in the slogans we chant, and in the types of television programmes we watch. If Thatcher commissioned TV drama, she would have programmed The Apprentice (I have to admit – I loved the first two series). Everything about it embodies the spirit of Thatcher’s hopes for Britain: the suave, easy freedom of the boss to fire employees, the mad dash for profit at any cost, the backstabbing and the competitive individualism.

At Trafalgar Square on Saturday, apart from the odd punk shouting ‘Maggie/Maggie /Maggie’ and then answering his own call with ‘Dead/Dead/Dead’, there was a strange unease and dampness to the day that had nothing to do with the rain. If the ambience could be condensed into a question it would read ‘What now?’ I came away with the sense that the biggest tragedy of yesterday is that Thatcher is more alive than ever.

AN EXAMPLE OF WHAT?

A female role model who shattered the glass ceiling, or a ruthless elitist who treated other women as subordinates? Bea Campbell knows which side she’s on

Let’s begin with the tribute paid to Britain’s first woman Prime Minister by the United States’ first black President Barack Obama: Thatcher, he said, ‘stands as an example to our daughters that there is no glass ceiling that can’t be shattered.’

But by then the prospects of a woman leading the Conservative Party in the House of Commons were as remote as before her election as leader in 1975. (Scottish Tories, however not only elected a woman leader in 2005 (Annabel Goldie) but a gay woman in 2011 (Ruth Davidson).

Obama’s comment was misleading.

Whereas Obama’s election mantra ‘Yes We Can’ was an affirmation of the electorate’s collective will, and a vindication of black Americans, Thatcher’s mantra might have been ‘Yes I Can’. She was an elitist, not an egalitarian: equality evaporated from her lexicon once she was elected leader in 1975 – ironically UN International Women’s Year.

She always addressed women as something she was not: as subordinate, as homemakers and private people. Women may have enjoyed her performance of power, but even her supporters regretted that she did not empower women or expand their room for manoeuvre in the party or politics generally. At the time of her death, the Conservative Party’s once awesome Women’s Organisation had shrivelled. It did not influence party policy. If individual women were inspired to become MPs, Thatcher had not encouraged her party to select them. Women comprised a pathetic 16 per cent of Tory MPs – below the 22 per cent average among European conservative parties, and well below Labour’s 30 per cent – the outcome of intrepid reform initiated during Thatcher’s tenure of Downing Street.

The notion of a glass ceiling presupposes that like Humpty Dumpty, once broken it could not be put together again. But if the ceiling is a structure, it works like a membrane that can expel or absorb an alien and spontaneously heal over. And so it was with Margaret Thatcher. The concept implies that individuals’ success or failure requires not social change, but merely an ability to withstand the institutions’ metabolic resistance to hitherto foreign bodies. The concept is as problematic as its partner in political crime: the role model.

Thatcherism’s patriarchal priorities are often excused as a problem of critical mass – there just weren’t enough women for her to promote; she would not have been allowed to get away with promoting women’s issues.

This is not sustainable.

Feminist political scientists have queried the notion of critical mass by showing that impact depends not only on numbers, but acts – exemplified by Thatcher herself: she triumphed, she was robust and ruthless.

The difficulty also derives from Thatcherism itself: its triumph was to enforce the lore of the market as the language of life. But that also marked the beginning of the end of the gender gap in favour of the Conservatives.

In the wake of almost obsessive national media attention after her death, Labour was 12 percentage points ahead of the Conservatives but 26 percentage points ahead among women voters. Research showed the complexity of women voters as a category, and the primary importance to them of social support, for relationships, for dependents, health and welfare – the very themes that were imperiled by the free market legacy of Thatcherism.

This is an extract from the introduction to a new e-book edition of Beatrix Campbell’s Iron Ladies, to be published by Virago in May 2013, reproduced by permission of the author and publisher.

A PATRIARCHAL PUPPET?

Feminists opposing Thatcher were always faced with a dilemma, argues Debbie Cameron.

If not ‘Iron Ladies’, what do we want powerful women to be?

In 1979, the year the British first put Margaret Thatcher into 10 Downing Street, I was a student in Newcastle, and just beginning to get involved in non-student feminist politics. In the north east at the time that meant socialist feminism; many of the women I knew were union activists and members of the Labour Party. It went without saying that we opposed Thatcher’s politics, but we struggled inconclusively with the question of how to do it without endorsing slogans like ‘ditch the bitch’, or pandering to the sexism which said a woman could not be Prime Minister.

This last week has been déjà vu all over again, as ‘Ding dong, the witch is dead’ ascended the charts and street parties were held to celebrate Thatcher’s demise. Despite my history as an anti-Thatcher activist, I found these responses disturbing. Not because of their disrespect for the dead or their insensitivity to other people’s grief, but because of their casual misogyny. Bitch, witch, Iron Lady — now as in the 1970s, the epithets are gendered. So is the visceral loathing behind the words: I can’t recall a male politician whose death has inspired proposals to go and dance on his grave.

It’s the Tories who’ve been emphasizing Thatcher’s gender, speaking openly about the prejudice she confronted when she started out, to make the point that she was a trail-blazer, someone who advanced the cause of women. (The BBC commentator on the funeral echoed the point, describing the Queen as ‘a woman who inherited her position honouring one who fought her way to the top’). What feminist commentators have mostly emphasized, meanwhile, is Thatcher’s difference from other women and the way her policies harmed women as a class. She was not, they insisted, ‘one of us’.

It’s possible that Thatcher herself would have preferred the feminist assessment. She was, after all, a rampant individualist, famous for her dictum that ‘there is no such thing as society’. But she was wrong about that, and the feminists who have suggested that her gender was an irrelevance are also wrong. Whether she liked it or not, she was judged as a woman; the hatred felt towards her was not gender-neutral. Rather it exemplified the general principle that when men act in ways we consider morally reprehensible they are condemned, but when women do the same things they are demonized.

Margaret Thatcher attracted the particular kind of loathing reserved for powerful women who exercise their power without apology or subterfuge, and are therefore seen as usurping men’s prerogatives. ‘Not a man to match her’, ‘the best man in the Cabinet’ — such assessments might have been offered as praise, but they still depended on the tacit assumption that legitimate authority is male by definition. For her detractors, the same assumption could be used to portray her as unnatural and monstrous. In the satirical TV programme Spitting Image, for instance, she was literally a woman in men’s clothing, her puppet dressed in a suit and tie; in many sketches the joke revolved around the way she emasculated the men in her Cabinet.

The undercurrent of misogyny that swirled around Thatcher throughout her career has been airbrushed out of the eulogies, presented only as one of the many obstacles she had triumphed over in the early part of her career (despite the fact that she was eventually removed from office not by the will of the British people, but by the men of her own party). But feminists should not forget it. Nor, however deeply her political legacy offends us, should we forget that Margaret Thatcher actually did do something that no woman before or since has done: she won power in her own right, and used it unashamedly to pursue her own agenda. She served no master, and feared no opponent. If feminists give her no credit for that, I think that isn’t only because we despised her brand of politics, it’s also because of our own ambivalence about powerful women.

What do we want, as feminists, from our female politicians? If not Iron Ladies, what kinds of women should they be? When I think about the available role models, it drives me almost to despair: loyal female lieutenants with no vision or personality (Margaret Beckett or Theresa May), self-promoting nonentities (Nadine Dorries), women who owe their political influence to their dynastic relationship with a man (Marine Le Pen, Alessandra Mussolini and — in case you think this is just a fascist phenomenon — the saintly Aung San Suu Kyi)—and don’t even get me started on the unelected ‘First Ladies’ who get so much attention in the media.

One female politician who seems to have acquired something of a feminist following is a fictional character: the Moderate Party leader who becomes Prime Minister in the Danish TV drama Borgen. To me, though, she is a depressingly reactionary figure: politically she embodies the ‘feminine’ desire for consensus, and in the course of two series her personal life goes to hell — her husband divorces her and her daughter has a nervous breakdown.

How did we get from Margaret Thatcher to this? Since she died I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve heard someone piously intoning that she ‘did so much for women in politics’, but when you look at women in politics what’s most striking is how little they resemble her. And I don’t mean that in a positive way: I mean that old habits have reasserted themselves, so that male dominance and misogyny are as entrenched in today’s political culture as they were before 1979. In office Thatcher was no token woman, but history might yet turn her into one. If so, it will show how little difference she really made to the underlying structures of patriarchal power.